Legal Aid celebrates life of legend, birth of library

Today, Oct. 11, Laurie Davison would have turned 75. By now, she would be retired or on the cusp of leaving an illustrious career at Legal Aid. Or, she might have headed a federal agency that had tired of facing her in court. Perhaps she’d have just closed the book on a storied judicial career.

“Our deal was, you stick around, I’ll stick around,” muses longest-running Executive Director of Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid, Jeremy Lane. For as long as she could, Davison did exactly that. Her start at Legal Aid began in 1977, leading the senior law unit. Soon after, she became a star litigator and one of the organization’s first litigation directors. “We agreed. I’d keep the doors open and she’d keep the lawsuits coming.”

For two decades, Davison used her extraordinary legal skills, identifying where system changes were needed. Successfully, time and again, she used her legal acumen on behalf of vulnerable public assistance recipients and broke ground, influenced changes in law and even took her arguments to the Supreme Court, twice. In her senior law and public benefits work, she made the case that federal entitlement programs should make things easier not harder for Minnesotans with meager earnings, many nearing the end of life.

Then one day, in November of 1996, she called, acknowledging the end of her own. “Out of nowhere,” Lane says, “she told me she had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. That was a very hard day. I knew, as she did, there was no happy outcome.” In January of 1997, Laurie was gone.

Her impact in life was far-reaching. In death, it remains so. Knowing Laurie profoundly but not personally was the experience of young attorney, Anne Robertson. “I came to Legal Aid in 1996. I did so for many reasons, but one of the biggest was Laurie Davison.”

When Robertson arrived, she discovered Davison had taken leave to convalesce. For Robertson, the gravity of occupying space within the same organization as her role model has stayed with her most every working day since.

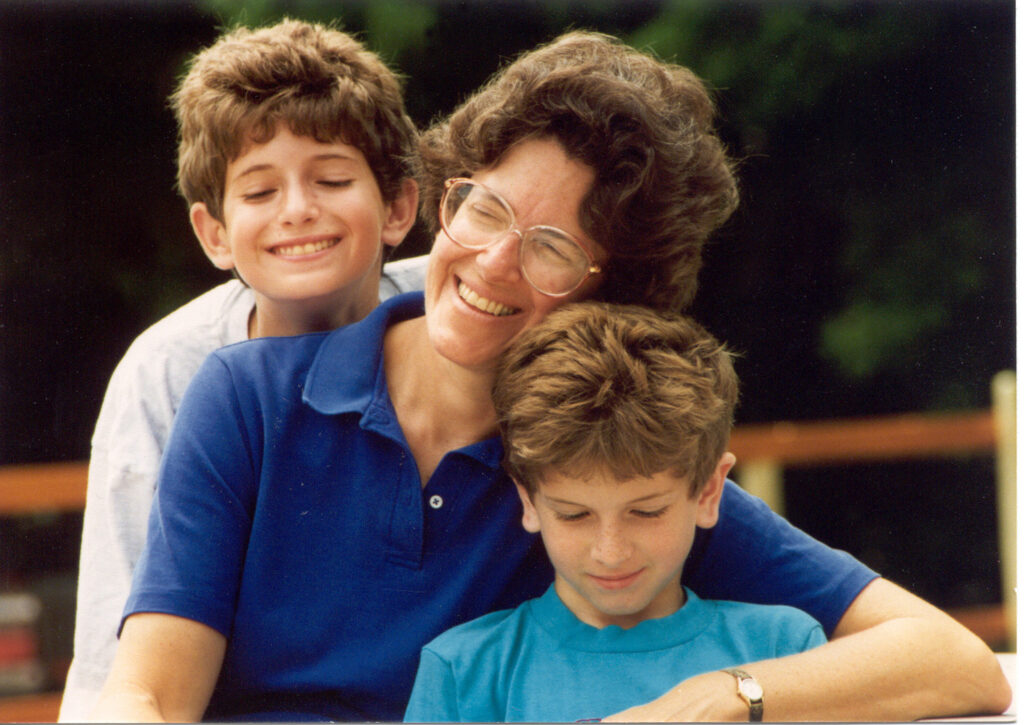

“When we moved from the Kickernick building across the street to new offices here in the Butler building, I was made the keeper of the Star Tribune news spread about Laurie’s life.” The print piece documented the impact of Laurie’s work and Lane’s eulogy. It also featured a photo of her with her young sons. Her husband, Dr. Scott Dyer, a fellow undergrad at Brown University where the two met at an organizing meeting to protest the Vietnam war, says that photo was her favorite. The laminated article had been on display in Robertson’s office since the move. Then, one day earlier this year, it found a new home.

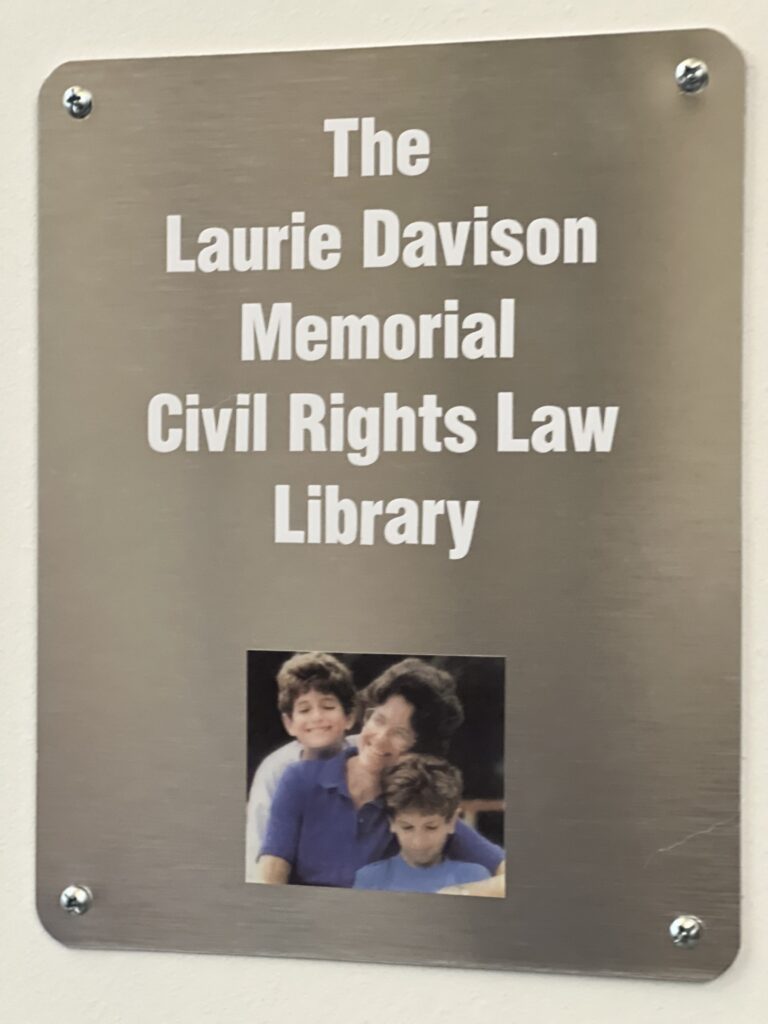

Realizing her longtime vision of a memorial library dedicated to Laurie, Anne decided to pick up an order of doughnuts and sent staff an email to gather on the third floor. In her corner hallway, she declared the area as the “Laurie Davison Memorial Civil Rights Law Library.” The laminated article now resides on the wall above bookshelves stacked and stuffed with legal tomes and files that represent the literal paper chase of hard-won, if not hard-fought, cases. Missing was a plaque. But in short order, it arrived, making the library dedication official.

Hearing about Anne Robertson’s reverence for Laurie’s memory and career, newly retired Deputy Director Ann Cofell says that admiration is well placed, “Laurie would be so proud of Anne and the work she does. She (Robertson) does it in the same way Laurie did with that passion for justice while also supporting lawyers with less experience and treating them well in that process.”

Cofell joined Legal Aid in 1980 and that’s when she got to know Davison, “I learned so much from Laurie. I remember being in a meeting with her and afterward, she said, ‘did you agree with what was happening?’ I said, ‘no.’ She said, ‘You have to speak up. When you speak, people listen, but if you don’t, you have no impact. That helped me to find my voice as a lawyer and as a leader.”

More than that, Cofell says Davison cared so deeply about people. “When she saw injustice, she saw the obligation of using our talents and skills to address that. She was such a great role model. One of the biggest cases I worked on was about a durational residency requirement. The legislature enacted a law which said newcomers to Minnesota would get less in public benefits than long-term residents and we worked together on that case challenging it as a violation of the constitutional right to travel and [violation of] the MN constitution. We won that case. It was appealed and went to the MN Supreme Court.”

“I told her inviting my parents will make me more nervous. She said no, you can’t be more nervous than you’ll be already.”

Deputy Director, Ann Cofell (ret.)

At Davison’s urging, Cofell reluctantly invited her parents to attend her oral arguments before the state’s highest court. She said, “You’ll want your parents there because no matter how you do, they will think you were wonderful.” Ann did end up taking her parents with her. She adds, “I’m so glad I did. And that’s just one example of how Laurie cared about me and others as a person, not just our legal work.”

Anne Henry, a 42-year veteran attorney with MMLA’s Minnesota Disability Law Center, arrived on the Legal Aid scene in 1975. She knew Laurie from the start, “Laurie felt this responsibility to share what she learned with everyone. She gave everybody everything she could in terms of support and her knowledge. She wrote articles for Clearing House (a national legal publication). She wanted all staff and nationwide legal services people to know what she had learned and to benefit from that.”

Supervising Attorney of Government Benefits Kathleen Davis worked alongside Davison and described her as someone who was always helping everybody. “She could have been a federal court judge, absolutely. She knew the law, she was creative, she was an excellent writer. I learned how to write from her. She could have worked anywhere, which is true of many at Legal Aid.” Davis says when Legal Aid decided to have litigation directors, “That’s where she blossomed. Her love was pursuing public benefits cases and health care law in the Medicaid area.”

“Everyone she touched loved her. She made you feel welcome. She encouraged you. When she argued (Gardebring v. Jenkins) before the U.S. Supreme Court, November of 1987, I remember about 10 of us tagged along. It was a thrill. The highlight was seeing her argue and catching sight of Thurgood Marshall in the hallway. It was such an incredible moment.”

Davis recalls the case was about Social Security. Laurie’s husband Scott adds, “It had to do with benefits being withheld because the recipient had received other funds that would have changed their income and disqualified them. But the state never informed recipients. They [the state] had failed in their due diligence.” That was Laurie’s argument. Dyer says she knew she didn’t have a chance because Justices Thomas and Scalia previously decided against that argument in a similar case. However, Sandra Day O’Connor, Dyer recalls, was impressed with Laurie’s arguments. “O’Connor ripped into the other attorney about the work they had done failing this group of people.”

Former Supervising Attorney Jay Wilkinson who pursued significant law reform litigation from 1978-2018, was mentored by Laurie, and reflects on her career saying, “It’s hard to single out one thing about Laurie when it came to achievements. She was passionate and respectful at the same time. Her calm, friendly demeanor meant it was easy to be her adversary without being her enemy.”

Lane sums up Davison’s gifts, describing her appreciation for the human condition, “She was a killer advocate. She did it by being civil, cordial, gracious. She had a better than average working relationship with lawyers. [This showed] If people like you, they’re not going to work quite as hard to beat you. Some lawyers think you have to have a take-no-prisoners attitude.” Laurie knew better. “She was a role model in how to live your life, not just how to be a lawyer. She was good at being a human being.”

Laurie Davison’s legacy of justice lives on through the Laurie Davison Endowment. Established by Laurie’s family, the endowment ensures a strong Legal Aid program today and for the future.